Australia is late to the space party. The leader of its new space agency, Megan Clark, said so herself. This continent, at the perfect location in the southern hemisphere to peer into the galaxy, has been one of the last developed countries to get a space agency, and she could not figure out why.

So, last year, Ms Clark led an expert review board to determine Australia’s space capabilities, and what they found surprised them. The size of the existing industry was much larger than previous estimates. And never before had Ms Clark seen stakeholders so united in a cause: The vast majority of players had been long clamoring for a space agency to act as a single Australian gateway to attract investment, support and guidance.

"And that makes your job really easy, because then you can go to the government and say 'The country is united, just take a step here. There’s no downside; there’s not one stakeholder that doesn’t want this'," Ms Clark said in an interview. "And it’s not a small group. It’s not a small voice. This is the nation that wants this."

The Australian Space Agency officially got its start a few months later in July — with Ms Clark named as its first chief executive. She now oversees a plan to triple the value of the Australian space industry to between $7 billion and $9 billion a year by 2030.

Ms Clark and her team have hit the ground running. The agency has signed memorandums of understanding with space agencies in France, the United Kingdom and Canada, been commended in a in the United States House of Representatives that promised further cooperation and signed a statement of intent with Airbus.

When the agency’s creation was announced, the public was a bit skeptical at its skimpy budget of $30 million over four years. That led to cartoons of boomerang-shaped rockets and internet jokes about a mock agency, , or ARSE. (By comparison, NASA’s budget this year is approximately $20 billion.) Ms Clark is unperturbed. To her, the size of the agency’s budget is not a terribly important factor in its immediate success. While NASA’s budget allows it to dictate to the American space industry, the goal of the ASA is to attract investment and create international partnerships, guiding the industry and uniting it under one national banner to help it grow — a role she says is much harder.

Ms Clark is unperturbed. To her, the size of the agency’s budget is not a terribly important factor in its immediate success. While NASA’s budget allows it to dictate to the American space industry, the goal of the ASA is to attract investment and create international partnerships, guiding the industry and uniting it under one national banner to help it grow — a role she says is much harder.

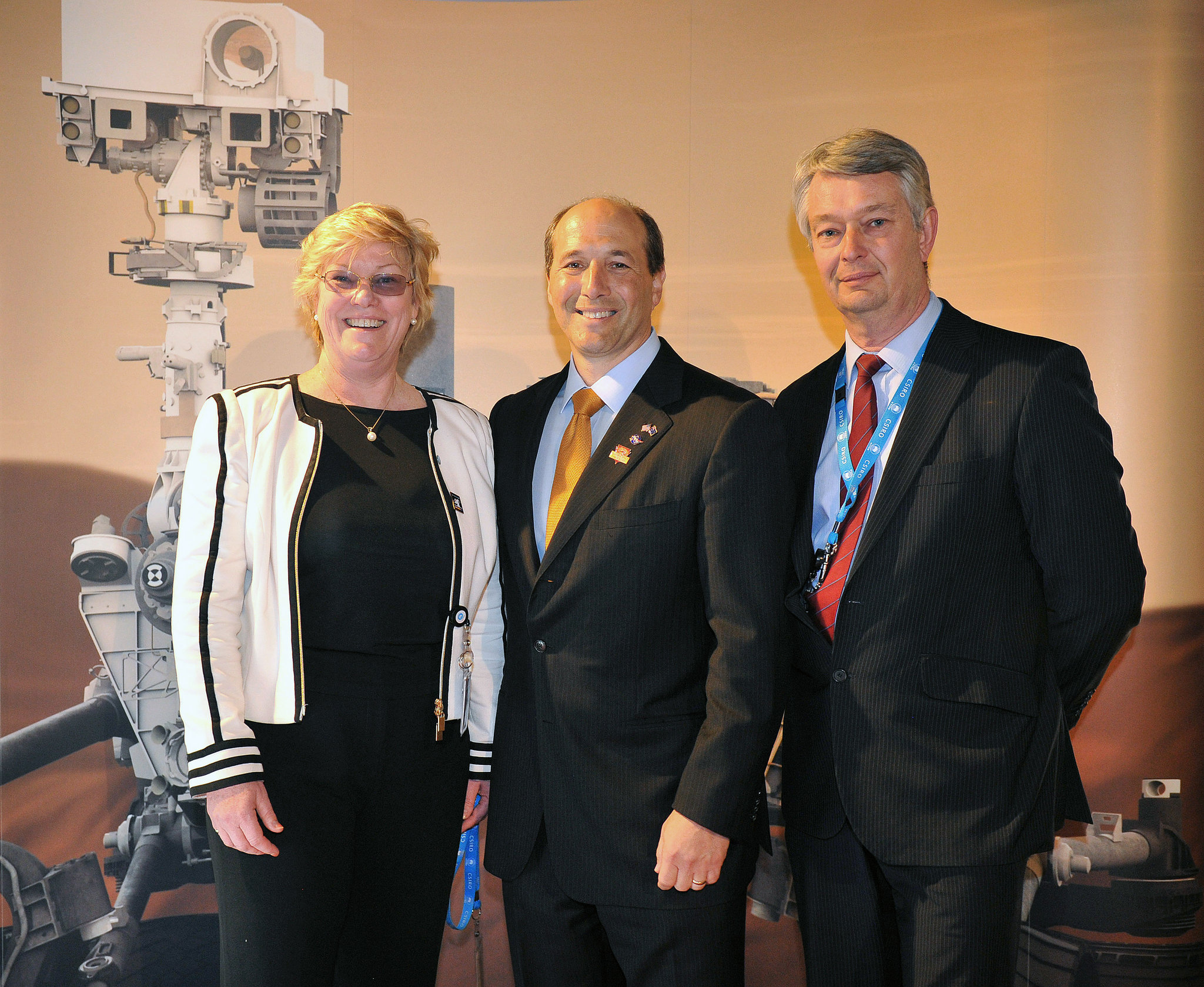

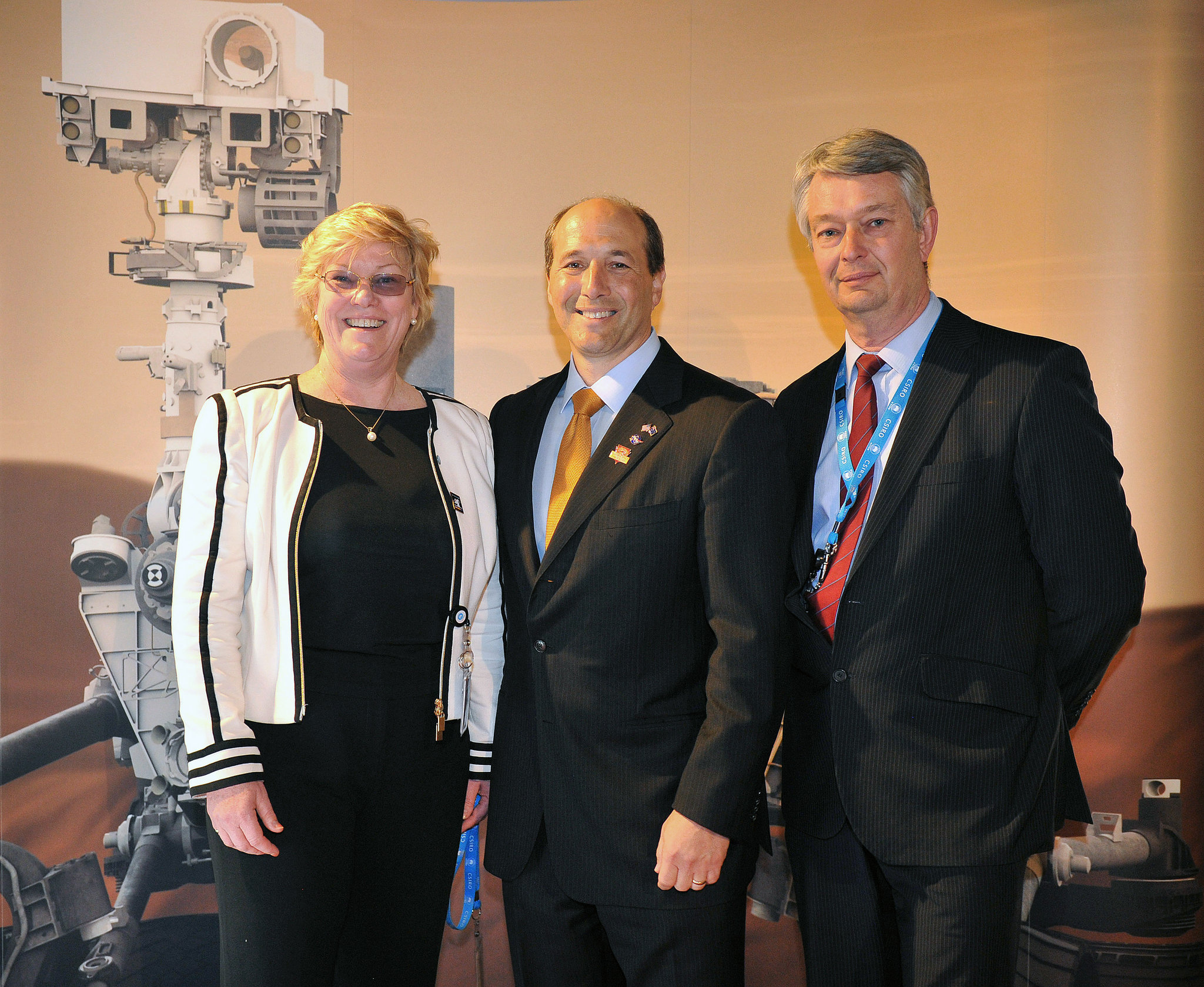

Megan Clark at the Canberra Deep Space Communications Complex in 2012 with its director, Ed Kruzins, right, and then US ambassador Jeffrey L. Bleich. Source: Mark Graham/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

"There’s an emerging shift in the role of government from that of sole funder to that of a partner and facilitator," said the newly appointed minister for industry, science and technology, Karen Andrews, in a speech during September’s Australian Space Research Conference. "These partnerships are expected to lead to new ventures, adding to the growing momentum in the industry."

Ms. Clark feels she is well equipped to guide the agency through its growing pains. Her career, which she calls "higgledy-piggledy", stretches from mining geology to venture capital to banking to becoming the first female chief executive of CSIRO, an Australian scientific research agency. Each one of her positions, she said, has been related in that it turned discovery into economic value — a major objective of most space agencies.

Like many of her colleagues, Ms Clark retains a childlike wonder at the mysteries of space, especially in Australia’s role in deciphering them. She spoke enthusiastically about witnessing the landing of the on Mars through the NASA-funded, CSIRO-operated deep space center near Canberra, Australia, when she was CSIRO’s chief executive. She raved about a virtual reality program from a Melbourne-based developer, Opaque Space, that caught the attention of NASA and Boeing Defense.

Her oft-repeated mantra for herself is "just do what’s in front of you". She’s climbed ladders in her career by tackling one task at a time, a pressure-combatting tactic she has attributed to an experience she had when she was 12. A doctor told her that if she did not get over the debilitating nervousness she was then enduring as a pre-adolescent, she would never be able to hold a stressful job as an adult. In a sense, she has devoted her life to proving that doctor wrong.

She is not one to let much inconvenience her pursuit of discovery, a trait that ran her into trouble in her early twenties: She was caught working in an underground mine in Western Australia, something that was then against the rules.

"The game was then that if a mines inspector came, you came up to the surface, and as long as they didn’t see you working underground or as long as you weren’t 'blatantly' working underground, they would sort of turn a blind eye," Dr Clark said. "And I just thought that lacked integrity: 'This is what I do, and I’m not going to hide from that.'" Her boss at the time was told to fire or relocate her, but he came to her defense and managed to get her an exemption, and the law was changed soon after in 1986. The experience was "confronting" but she does not regret doing her job.

Her boss at the time was told to fire or relocate her, but he came to her defense and managed to get her an exemption, and the law was changed soon after in 1986. The experience was "confronting" but she does not regret doing her job.

A radio telescope in Parkes, Australia, that was involved in the Apollo 11 mission. Source: Torsten Blackwood/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Ms Clark grew up in Perth, the most isolated capital city in the world and what she calls "the last capillary of the global network". She felt there were only two career options in Western Australia promising a ticket to the world: mining and oil. She chose mining.

She has a strong sense of adventure, a trait she says is quintessentially Australian, and was gripped by the sense that "the world is out there, not here". She chose where to do her Ph.D. in economic geology — Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada — by finding out where you would end up at if you stuck a pin straight through the globe from Perth.

Now, she says, the next generation of Australians should harness that adventurous instinct to travel beyond the planet, not just to the other side of the world. The opportunities for Australians to enter the space market have evidently been slim — all three Australian astronauts received American citizenship and went to work for NASA — but now she wants to bring the lost potential back.

Her busy schedule makes her forget, sometimes, just how influential her presence as the head of the space agency, and as a woman, can be. But she has received an influx of letters from young boys and girls alike that remind her of the power space has to inspire youth.

"You see that in space, that curiosity you had as a kid. Some people get it beaten out of them, but some people don’t, and they end up in the space sector," she said. "That curiosity is really important, and that sense of being a child and being able to be a bit nerdy about it."

Australia might not launch its own rocket to Mars any time soon. But she’s confident she'll see a human on the red planet within her lifetime, and she hopes an Australian will be among them.