The Feed built a fake influencer account in order to take a closer look at influencer marketing. The six-month investigation exposed a culture of hidden advertising, with influencers, brands and agencies ignoring regulations and laws designed to protect consumers.

Mia Wilde’s Instagram feed, with its 84,000 followers, inspires aspiration.

Smiling beach selfies, organic home-made food (Aleppo chilli flakes, always!), cute dog, handsome surfer boyfriend, occasional promo for coconut water or detox tea, meditation.

But @thatcoastalgirl is not your typical influencer on the rise.

In fact, she doesn’t even exist.

The fake Instagram account was built by two journalists, myself and Calliste Weitenberg. (FYI we don’t live anywhere near the sea.)

So how did we get here, and why? Scroll through your Instagram feed and see if you can work out what’s an advertisement and what isn’t.

Sure, sometimes it’s clear - the post might be tagged with #ad or #sponsored, or “paid partnership”. But what about the influencer chatting in her Insta stories about some “amazing” hair vitamins that “really work”? Or wearing activewear that she swears “really doesn’t chafe”?

Or drinking a hardcore gym pre-workout because “it just tastes good”?

And it’s no longer just the Kim Kardashians of the world pimping products in their feeds.

Brands, including small businesses, are now chasing what are known as micro-influencers. With less than 100K followers, these people could be your neighbour, your sister, your personal trainer. They ooze authenticity, and you trust their opinion on everything from ready-to-eat meal brands to why a penis-shaped crystal in a water bottle is going to improve hydration.

It’s social media’s “dirty little secret”, according to former Instagram star Essena O’Neill. “If you weren't selling products, what would you be doing? What would you be talking about?”O’Neill shut down her accounts at the height of her fame in 2015 and has stayed off ever since.

“I think the only way you'd ever understand just how crazy this world is, is if you become an influencer yourself,” she told The Feed.

And so, that’s what we did.

In October 2020, we set up @thatcoastalgirl with Calliste as the face of it. Creating a fake account was the only way we could truly understand what’s going on inside the world of sponsored content - and show what this means for the many Australian businesses investing in influencers, for consumers, and for those chasing the influencer dream.

We decided on a breezy lifestyle/wellness influencer because it’s a space that brands are really active in.

We spent a day and a bit taking pics at the beach and some cafes. We were naive enough to think that would be enough.

Turns out being an influencer is a time-consuming, energy-sucking form of drudgery where everything you do, and everyone you love, ends up being turned into content. You have to post multiple times per day, and not just photos but also short videos for stories and reels that take ages to edit.

Kudos to the Instagrammers who really do this. Early on, we started crowdsourcing pics and clips from friends.

In order to get brands interested in our account, we knew we needed at least 2,000 followers. Within a month we realised just how hard this would be - at about 180 followers our growth stagnated.

Growing an account organically on Instagram is really difficult these days. You either need to have content that goes viral, or pay Instagram to promote your posts. This makes sense. Instagram (owned by Facebook) is a business that wants to make money. Unless you’re doing something that will help it do this, then you won’t be receiving a free ride.

So, instead, we did what a lot of other wannabes do to kickstart their accounts. We bought 2,500 followers from a dodgy website that promised they’d be “genuine” and “real users”. In fact, they all appeared to be fake - bots and clones of real accounts.

We also bought likes and story views. And we joined engagement pods - these are chat groups where you all agree to like and comment on each other’s posts. Many of the people we met in these groups were, like us, just starting out and trying desperately to get traction.

says Alex Frolov, founder of HypeAuditor, a business that specialises in detecting influencer fraud on behalf of brands. He says globally, nearly half of all Instagram accounts are suspicious and could be bot accounts made by those who sell followers.

Instagram says it routinely cracks down on these dodgy accounts, and engagement pods. But our experiment proved that cheating the system is still common and easy to do.

Once we had more than 2,000 followers, the sponsored content (or “sponcon” as it's known in the industry) began to roll in: from coconut yoghurt to magnetic eyelashes, underwear to swimwear.

These involved free products - not paid deals. We signed up with an agency that connects influencers with brands via an online platform, called The Right Fit.

They say they vet the influencers on their platform to ensure they’re not involved in influencer fraud. But we had no problem signing up and getting products through them. Other freebies came from brands who messaged us directly. This included some skinny tea with “natural appetite suppressants”.

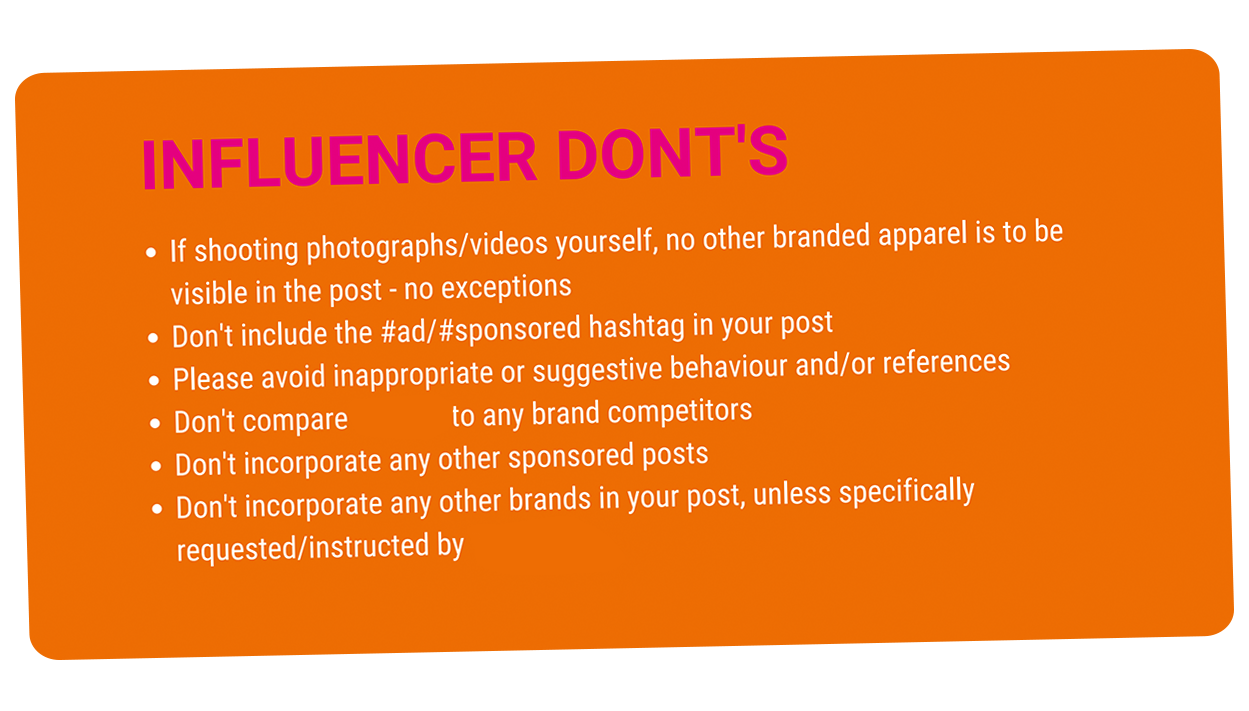

In return for the free products, we were expected to put up posts featuring them. Essentially, advertisements. Brands would often send a brief outlining what to say. Only one brand told us to include the tag #ad or #sponsored.

And then there was a company that we got a deal with via The Right Fit, that specifically told us not to label the posts as sponsored at all. In a statement, The Right Fit told us, “We will always do our best to vet any account that misrepresents themselves and will also always provide this information transparently to all clients via the analytics tools to empower them to make an informed decision as to who they work with.”

But not labelling sponsored posts goes against the industry’s own guidelines and potentially violates consumer law.

There are two sets of industry codes that outline how sponsored posts should be labelled in Australia. They specify that all sponsored posts should be clearly labelled with either #ad or #sponsored and commercial relationships should be made clear.

And under Australian consumer law, advertising is not allowed to be misleading or deceptive.

So, if you put up a post saying a product has made your hair grow thick and fast when it hasn’t, then that’s misleading, according to Rebecca Dunn from Gilbert and Tobin. And, “if you post something about hair products and you don’t disclose that you’ve been paid to do so, that could potentially be misleading.”

In the US and UK, authorities have been cracking down on brands and influencers who don’t disclose a commercial relationship, or use deceptive claims in their posts. A detox tea company was fined $1 million in the US, and the Federal Trade Commission has sent warning letters to influencers.

The consumer regulator here, the ACCC, can apply a penalty of up to $500,000 for an individual, or $10 million for a company, but they haven’t yet brought a case.

In a statement, The Right Fit told us they “provide education to both sides of our marketplace on industry information relevant to our users”. In the influencer space, they say this includes education on “things like the AANA (Australian Association of National Advertisers) guides and how to use In Paid Partnership on Instagram for example”.

When we approached Instagram, they declined an interview and did not respond to our questions. In a statement they said, “We have strict policies on Instagram which require disclosure tools be used in all instances where posts contain branded or commercial content”

When we revealed our account was all a charade, some of our genuine followers commented on the post.

So why does any of this matter?

Who’s being harmed if an influencer fails to label an ad?

Well, towards the end of our journey, we met Niki Reed who has struggled with an eating disorder for more than a decade. Last year, she was hospitalised twice after severely restricting her diet.

Over the years, Niki has bought diet products and fitness plans after seeing them spruiked by influencers.

“They share parts of their life to make it seem like they've got this real intimacy with you, so you do have this level of trust and you become susceptible to the products they sell,” she told us.

Niki says full disclosure of advertising on social media is an important “circuit breaker” for followers. It’s a reminder that “it’s not a real person with a supplement that they're recommending because they've used it for them...this is paid-for content”.

Throughout the process, care was taken to make sure any impact to Mia’s followers was minimal.

Watch the last instalment of Calliste Weitenberg & Elise Potaka’s four-part series on the influencer industry on The Feed at 10pm tonight on SBS, and catch up on the whole investigation on SBS On Demand.