WARNING: This article discusses themes that may be distressing to some readers.

Gayiri Country is beautiful, in the way that only some of the most rural parts of Australia can be.

The dryness in the heat, in the ground, and the river banks are both delicate and concerning.

The Country is mountainous, paddocks stretch out below as we fly in - the only patches of green in a landscape of red and brown.

The heat is oppressive and the streets are quiet, possibly because we’ve arrived in town in the warmest part of the day.

But it’s also unsettling, especially considering the reason I’m here. Over 160 years ago - at least 300 Gayiri people were murdered on this Country.

Over 160 years ago - at least 300 Gayiri people were murdered on this Country.

Sunrise on Gayiri Country in central Queensland. Source: NITV The Point

Shot. Driven off cliffs. Massacred indiscriminately.

I’ve travelled to Central Queensland after reports alleging cricket and AFL pioneer Tom Wills participated in these attacks on Aboriginal people, in retribution for a massacre of white people at his family’s camp.

What I found was this story holds so much weight for the locals and still triggers a range of emotions.

In 1861, 19 settlers were killed on Cullin-La-Ringo station in Springsure, Central Queensland.

The retaliation attacks on Gayiri are the lesser-known part of the story, but for local Elder Darryl Black, it’s important that people know the whole history.

The Gayiri man learned about the massacre from his father.

“I love this country here but you get this funny feeling when you come here, like something upset everybody here,” he says.

I feel the same funny feeling I have felt since I got off the plane. It’s like I can physically feel the sadness in my chest, the heaviness of this Country. Uncle Darryl welcomes my camera operator and I to his Country and bathes us in sandalwood smoke for protection.

Uncle Darryl welcomes my camera operator and I to his Country and bathes us in sandalwood smoke for protection.

Uncle Darryl performs a smoking ceremony for my cameraman Terry and I. Source: NITV The Point

“When I get the smoke going, I want you to stand in the smoke and wash yourself like you are having a bath,” he says.

He feels it’s his mission to teach others the truth about what happened here.

“The Wills massacre was the biggest massacre of white people in Australia’s history," he said.

“What people don’t know is that after that they came and slaughtered our people, out of the seven tribes on Gayiri Country, they slaughtered five straight away.

“Most of our people were killed here on this Country.” There is a memorial to the 19 dead settlers at the site of the Cullin-la-Ringo massacre.

There is a memorial to the 19 dead settlers at the site of the Cullin-la-Ringo massacre.

The view from Springsure lookout. Source: NITV The Point

But nothing for the more than 300 Gayiri people massacred in response.

Even today the Country is unsettling, and its eerie calm brings my cameraman to tears.

I grew up listening to stories of massacres on my own Gamilaroi Country; my father, my grandparents speaking truth to our history.

Through my work, I’ve visited a number of massacre sites. I know the feeling, and it’s something you never forget.

The recent allegations surrounding Tom Wills have frustrated Darryl, who says he’s been trying to draw attention to these events for years.

But he adds, the history is not as clear cut as is being reported.

“Thomas Wills we always think he was a great man and was a great friend to the Aboriginal people so I wouldn’t want to see his name distorted in any way like that,” Uncle Darryl says. The killings started over some sheep, which disappeared.

The killings started over some sheep, which disappeared.

Uncle Darryl Black shows us some artefacts he's found on Country. Source: NITV The Point

The local people were blamed - and Uncle Darryl says the Wills’ neighbour Jesse Gregson shot a number of Aboriginal people.

Afterwards, he didn’t ride straight home but went to the Wills’ camp - leading the Aboriginal trackers, who had come for retribution, there.

“What happens then is the young bucks have been out hunting for the day and they come back to find their people have been shot… so they send out smoke signals to a neighbouring tribe over on Snake Range and they came over to track the people who killed their people,” Uncle Darryl says.

“They followed the tracks and these tracks led them straight around to the Wills camp.

“The local mob pulled up and thought these can’t be the people, we got along good with these people but the group they invited went straight in and slaughtered them straight away, in minutes, it was that quick and fast, from that, that’s where the massacres started.”

A difficult story

Historian and author Frank Uhr tells a similar story of the events that unfolded.

He believes the shepherds had fallen to sleep and their sheep had wandered off. To cover up their mistake they’d lied and said they were attacked by Aboriginal people and the sheep had been stolen.

“The local squatters, not Wills, organised a vigilante group,” Mr Uhr says.

“They went and found the local clan, the nearest clan they could find, without thinking, without asking questions, without looking for the sheep, without understanding anything that went on, they just started shooting, they killed 20 people.”

Frank said the attack on Cullin-La-Ringo following this killing was done “quietly, quickly and with utmost effect”.

And the reprisals after that were “horrific”.

“The local stations organised vigilante groups,” he says.

“They started pushing the Aboriginals up into a mountain area or a hill area. As they were about to attack or be attacked by the Aboriginals coming back down the hill the native police came in and that was disastrous.” The base for these vigilante attacks - Rainworth Station, was owned by Wills’ neighbour Gregson, he says.

The base for these vigilante attacks - Rainworth Station, was owned by Wills’ neighbour Gregson, he says.

Sunset on Gayiri Country Source: NITV The Point

“There’s a famous stone fort on Rainworth station which was probably a storehouse of some sort, which they’re fabled to have turned into a fort,” Mr Uhr says.

“Gregson owned Rainworth at that stage and that became the base for the reprisals too.”

The story is difficult, and, like many events of the time, there are multiple versions of what unfolded.

Uncle Darryl believes telling the truth about the history will lead to the eventual healing of his Country.

“I’d like to see a sorry day for our mobs here, white and black,” Uncle Darryl tells me.

“We all sit down together, have a big sorry day, have a barbeque and we all come together and face each other and shake each other’s hands.

“We both apologise for the way things happened in the past, and we can shake hands and then move along.

“The truth needs to be told. We can’t keep living a lie.

“No one wants to speak the truth about what’s happened in our past.”

After visiting Gayiri Country, feeling the sadness, the pain it holds 160 years later, having these conversations feels like a difficult but essential task.

While talking alone could never heal this pain, speaking the truth - and listening to it - seems like a good place to start. Watch The Point story here:

Watch The Point story here:

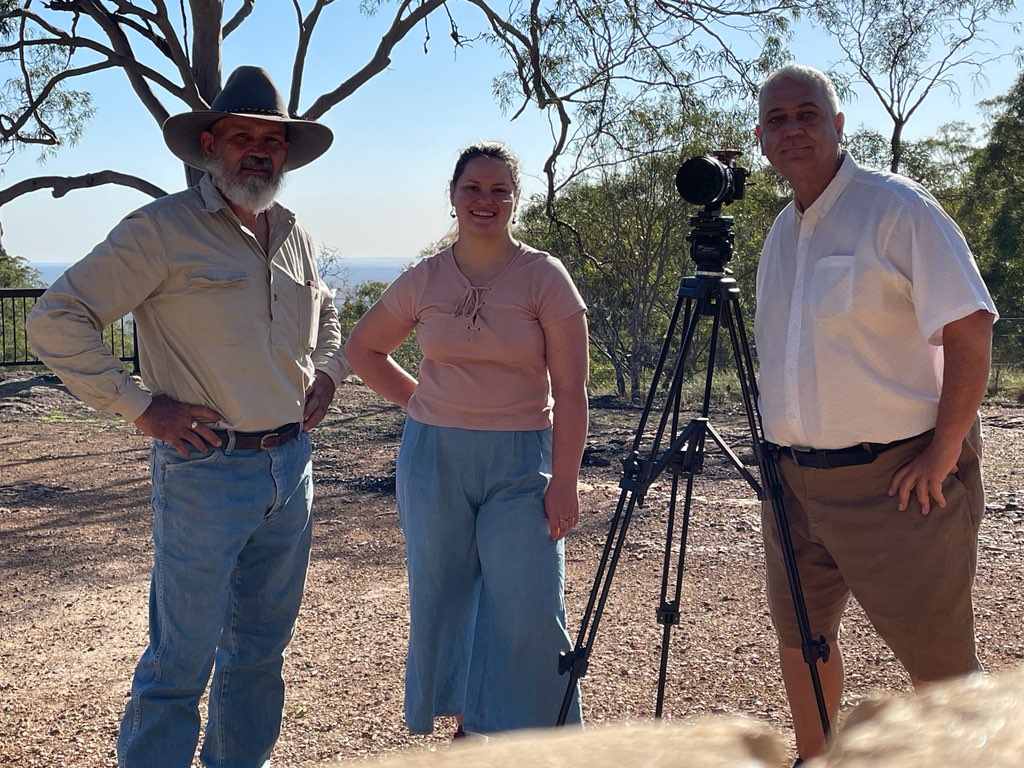

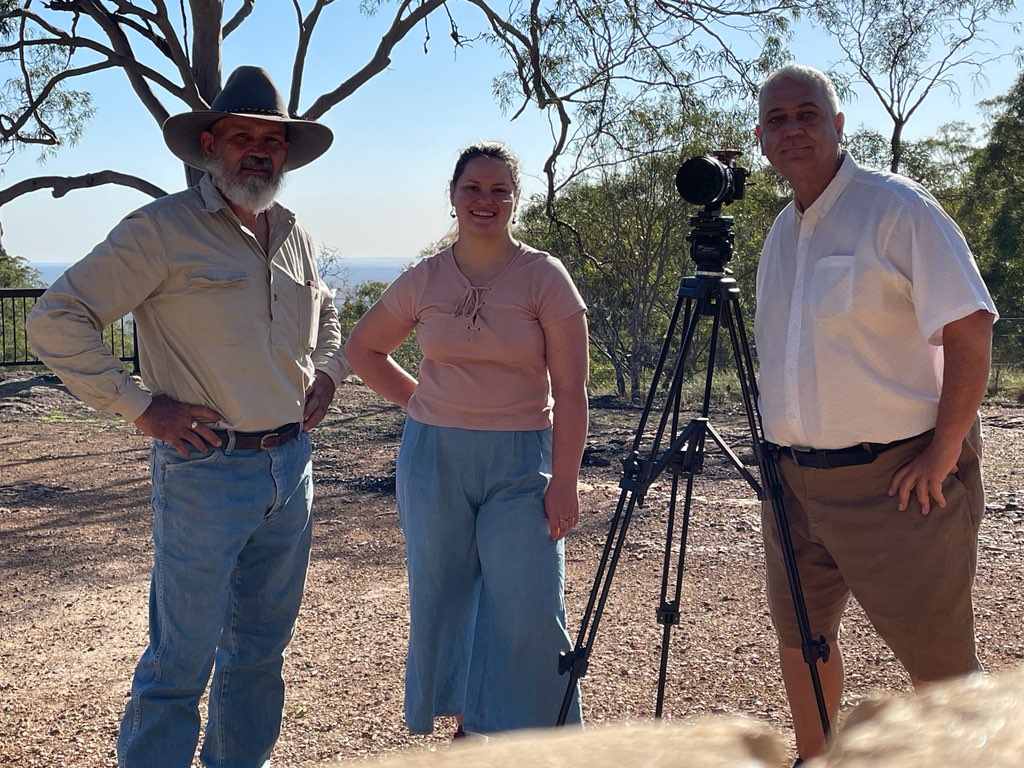

Uncle Darryl shows cameraman Terry and myself around his Country. Source: NITV The Point